“People who are winners are engaged in making things happen and are not consumed with hatred or putting others down.”

“Every single American in this country has to dedicate him or herself to being the best person that they can be to help this country live out its creed.”

George Taliaferro was one of the few African Americans to attend Indiana University in the 1940’s. In 1945, his freshman year, he led the IU football team to their first Big Ten championship. In 1949, he would become the first African American to be drafted by the National Football League and would become the first African American to play quarterback in the history of professional football.

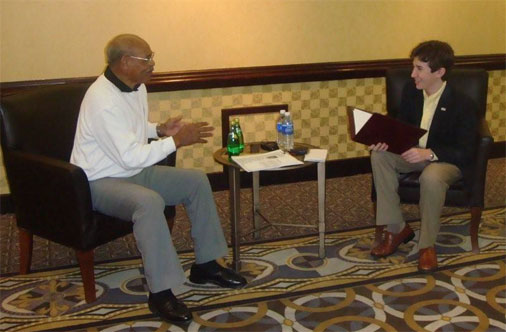

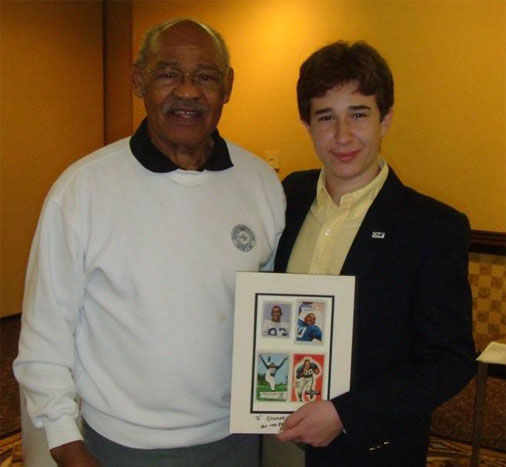

In 2009, sixty years later, George Taliaferro and his wife would be guests at Super Bowl XLIII. The interview took place before a small gathering, the day before the big event.

|

Spencer: |

I am happy to introduce to you George Taliaferro, who has come to Tampa to support my project, Stoves For Darfur. Tomorrow, we will not only celebrate Super Bowl XLIII, we will also kick off Black History Month. We welcome George Taliaferro, the first African-American to be drafted into the NFL and the first African-American to play quarterback in professional football.

In 1949, 60 years ago, you learned you had been drafted by the Chicago Bears. Former coach of the Indianapolis Colts, Tony Dungy, has said, "Every African-American in the NFL today owes you a debt of gratitude." What do you believe was your impact on the NFL?

|

George Taliaferro: |

The fact that I was one player who could play any position, any skilled position in football and be better than or as good as anybody in professional football, was one indication that African-American youngsters could play the game.

|

Spencer: |

You went from the inner city of Gary, Indiana, to the segregated campus of Indiana University in 1945. What was it like being an African-American student athlete in a southern Indiana college town in the 1940s?

|

George Taliaferro: |

It wasn't bad as far as being an athlete was concerned. The problem that I had was adapting to be a second-class citizen. Indiana University invited me as a football player, not as a human being. There wasn't anything that I could do in the city of Bloomington or on the campus at Indiana University except attend classes and play football. It was extremely difficult.

I stayed in my room one Saturday all day long. I did nothing but try to work myself through whether I was going to remain at Indiana University's campus or go somewhere else, and the only other colleges that I could've attended were traditionally black colleges. I couldn't even attend the University of Notre Dame and that was 60 miles from where I lived. I couldn't attend Purdue University, both in the state of Indiana. What I decided was, being discriminated against because of the color of my skin was a small price to pay to receive a quality education, and that's what I did.

|

Spencer: |

Did you experience Jim Crow problems, things on the road from opposing players and families, that maybe young African-American athletes today don't have to think about?

|

George Taliaferro: |

They don't – African-American youngsters today have no idea what men of my ilk had to go through in order just to play the game, and my motivation was I wanted to play football worse than the Lord wanted sinners. So I was willing to go through hell or high water, as the case might be, just to play football, and that's what I did.

|

Spencer: |

The Gables Restaurant on the Indiana campus had a large picture of you and the 1945 championship team on the wall. But I understand you were not allowed to eat there because of your race. Could you explain how this famous student hangout eventually became integrated?

|

George Taliaferro: |

It was integrated and I have to give you an altered story. I thought I was the motivation for them to integrate it but the NAACP, the Indiana University chapter of the NAACP, had instituted a suit – unknown to me and I was a member. But what happened to me was, I had a class on one side of the campus, let's just say a half a mile from my home. I had a class that ended at 12:00. I had to run that half a mile from that point to where I lived in Bloomington in order to have lunch but I had to return to my next class at 1:00, which meant that I was in pretty good physical shape because I had to run to eat. One day, I got the brilliant idea as I was running past the administration building to stop in to see Dr. Herman Wells, who was the president of Indiana University and had an open policy. Not even halfway out of breath, I went up, knocked on his door, his secretary asked me to come in and asked me my name and I said, "George Taliaferro." By the time the sound of my voice fell off, Dr. Wells was standing in the doorway of his office and asked his secretary, "Did I hear the name George Taliaferro?" I said, "Yes, sir." He said, "Come right on in." He had an open-door policy. I got right to the point. I said to him, "I have $1.25 in my pocket and I can't eat anywhere in the city of Bloomington." He said, "Let's see what we can do about it." He picks up the telephone and the Gables Restaurant was right across the street, just a little bit further than that door. He said to the owner, "George Taliaferro and I would like to have lunch at your restaurant." Now, he's on the telephone so I couldn't hear the response. I would imagine it went something like, "We don't allow the colored students" – 'cause we were colored then; we weren't black 'cause you called us black in those days and you'd have to fight – 'cause I would fight – but "We don't allow the colored students because we're here to make a profit and we don't know what the reaction of the white students would be if we allowed the colored students to come in." So Dr. Wells said, "Then I might have to make your restaurant off limits to all students." Case closed. The restaurant was integrated.

|

Spencer: |

The Chicago Bears drafted you in 1949. You grew up near Chicago, dreaming of playing for the Bears, but you turned them down. Could you explain why?

|

George Taliaferro: |

My dad had a fourth-grade education. My mother had a sixth-grade education. My father never told me to do anything. I was one of five children, the second oldest. My father asked me to dig up a plot of ground about three-quarters the size of this room so that he could plant his garden. People in Gary, all people, mostly all people, had little gardens that they grew tomatoes and potatoes and corn and that kind of thing, and my dad had asked me to dig up that plot of ground on a Saturday so that when he got home from work, he could start planting his crop. Of course, I said yes.

Some of the guys in the neighborhood came by and said, "Let's go swimming, and when we come back, we will help you dig up the ground." You didn't think I was gonna turn that down – no way. I go to the swimming pool. Didn't have a watch and there's no such thing as – what are these little –? Cell phone, yeah – no, nothing such as a cell phone. It was a quarter of four and my father's going to be home at ten minutes after four. I did not beat my father to our house. He walked through our home onto the back porch and did not see that ground turned over and he motioned to me with his finger, "May I speak to you?" and I said, "Yes, sir." He said, "A man is no more, no worse, than his word," and he never spoke about that incident again in his lifetime.

I started digging that plot of ground up at 4:30 and it was 4:00 a.m. before I finished. My mother stood with a lantern while I continued to dig that plot of ground up because I said to my mother, "He will never have to say that to me again." I became a man when I was 12 years of age.

I had already signed a contract to play with the Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference in 1949. I was in Chicago with a group of 12 or 13 other pro ball players, working out. We then decided, after the workout, to go to a restaurant for lunch. We were able to shower and clean up, go to this restaurant, and there were three guys that I'd played against in high school that were now pro ball players: Buddy Young, who was the fastest man in the world at that time – 5'4" tall, 170 pounds, but like all bullets, very quick; Sherman Howard; and another fellow named Earl Banks.

Well, Howard and Young and I went to the restaurant to eat. Banks went to his home. He was from Chicago. Banks comes in maybe a half hour later and just says to a group of 13 of us, "Guess who was drafted by the Chicago Bears?" Well, all 13 – there were five black players and eight white players – all of us started to name outstanding college football players, but the one thing they had in common in was they were white. Banks is standing there with his hand behind his back. You don't make any note of it because he's a funny-looking guy and he might stand any kind of way. He then comes out with the Chicago Daily News paper with three-inch square letters: "Taliaferro Drafted by Bears."

I never spoke to the Chicago Bears about signing a contract. I spoke to my mother. My dad, unfortunately, had died by that time and I said, "All I have to do is tear this contract (with Los Angeles) up, give them their $4,000.00 back, and I can play with the Chicago Bears." I had dreamed that I would play with the Chicago Bears, and I told everybody in the city of Gary who would listen to me, I was going to be a great football player but I was going to play for the Chicago Bears. There weren't any African-Americans playing professional football. None. What gave me the idea that I would be Numero Uno?

You can dream, but then at some point in time, you have to pay the fiddler if you are going to have your dream come true. And my mother reminded me, "What did you tell your father about being a man? You gave your word to the Los Angeles Dons. You make the decision." That's why I never played for the Chicago Bears. I wanted to, but I was more in tune with the wisdom that my father left with me. I honored my word.

|

Spencer: |

You've said that during your first year in pro football, you sometimes threw the ball around with an 11-year-old boy who hung around the practice field. Could you tell us who that boy was and a little of the story?

|

George Taliaferro: |

I found out in 2005 in the city of Baltimore at a banquet put on by Lenny Moore, who is a former Baltimore Colt and is in the Football Hall of Fame. My wife and I were seated in what I guess the television people call the green room (you're getting ready to go out) and I heard a person ask some of the older Baltimore Colt former players, "Is George Taliaferro here?" One of the guys pointed and said, "There he is right over there." So, this gentleman comes and kneels down and doesn't even look at me. He looks at my wife and says, "My name is Jack Kemp. Do you know –" and Vi says, "Oh, I know who you are. You're a Congressman from New York."

Well, by that time, he was out of Congress. It was Jack Kemp who today is a lobbyist in Washington, D.C., and who became an NFL quarterback with San Diego and Buffalo, I believe it was. It was Jack Kemp. Jack and three of his buddies, age 11, would hang around football practice when I was playing with the Los Angeles Dons. Jack and his buddies were always there to have me throw passes to them, because that was one of my specialties. And it was Jack Kemp who told me that story. I remembered the youngsters instantaneously because it was something that helped me to prepare for professional football games. Four little guys that I threw passes to, and one turns out to be a magnificent human being.

|

Spencer: |

Other African-American quarterbacks followed you: Willie Thrower, Charlie Brackens, Marlin Briscoe, Shack Harris, and Joe Gilliam. For decades, there were only a few African-Americans who played quarterback. Doug Williams joined Tampa Bay in 1978, and ten years later, led the Redskins to a victory in Super Bowl XXII. Many outstanding quarterbacks were to follow. Why did it take so long?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Because the United States – and I use that term to make it all-inclusive, not just the team owners, but the United States didn't believe that an African-American youngster could be the general, could perform the duties of a quarterback. I demonstrated that I, as an African-American youngster, could do anything that needed to be done on the football field and do it better or as well as anybody else. Doug Williams, Shack Harris, and Marlin Briscoe never referred to me as having been the first African-American quarterback in professional football, nor the National Football League. I first played quarterback in the All-American Football Conference and they give me the impression that they founded the position of quarterback in the National Football League, which wasn't so.

|

Spencer: |

One way African-American players were held back was a practice called stacking. Could you explain that?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Stacking means having all African-American players to play whatever position was open. If you were a running back, you all played the same running back position – and I go back a long time ago when running backs were given specific designated names (right halfback, left halfback, and fullback) because this was a way the T formation was set up, and stacking was a matter of having all of one color play one position. If it were a tackle, every African-American played that tackle because it limited the number of African-Americans being used.

|

Spencer: |

You have discussed some unpleasant incidents, including a confrontation that occurred in a game between New York and the San Francisco 49ers. Could you share that story?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Yes, and I laugh a lot about this because I have heard the response of the young man who was involved. He was a graduate of LSU. On our football team, the New York Yanks, we had – our fullback was a big guy from LSU. He had said to me, "Be careful of this guy. He has some bad attitudes as far as race is concerned," and I said, "What is that going to have to do with this football team?" Well, I found out. I punted the ball. This little guy, his name was Sam Cathcart, caught the ball. Sam must've been 5'10", 165. I was 200 pounds at that time and willing and able to kill anything old enough to die.

He catches the punt and gets behind a wall of blockers that created a gauntlet through which he could run. I happened to get inside of that gauntlet because I was the last bastion of defense. As he approached me, he jumped as if to kick me in the face because we did not wear face masks in those days. I avoided the kick in the face with my forearm, which flipped him on his back. No face mask. I shot two kicks to his nose that just burst his nose wide open, and I got up and the game went on.

Now, I have heard a retort from Sam Cathcart regarding that incident and he recalls that he had intercepted a pass. There's a little bit of difference between kicking a football and throwing one. He didn't know the difference, and he said– and these are his words – "I attempted to leap over his head." I'm six feet tall and he's got on all that football equipment. How in the hell is he going to leap over my head? Well, it cost him a busted nose. He defaulted. He wasn't able to carry out his mission but I did mine.

|

Spencer: |

The Washington Redskins were the last NFL team to integrate. Once, when you were with the Colts, George Preston Marshall, who was the Redskins owner, said something to you during the pre-game introductions. Could you explain that incident?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Well, you have one part of that that's wrong. He didn't say anything to me. I was standing as the last offensive player to be introduced to the crowd in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1953. The Baltimore Colts were playing the Washington Redskins, an exhibition game, and as I was the last offensive player to be introduced, the other teammates of mine had gone on through the goal posts to the applause of the crowd, and George Preston Marshall must've been standing, I'd say, ten feet behind me, waiting for his football team to be introduced. And what he said was, "All niggers should be made to push wheelbarrows and that's all." He said it loud enough for me to hear it.

I scored three touchdowns that day, and I could not get across the field to where he was standing before he was ushered out of that place because I wanted to ask him if I had pushed the wheelbarrow fast enough.

|

Spencer: |

You were chosen to play in the Pro Bowl three times and retired from professional football in 1955 due to injuries. Did you accomplish what you wanted to?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Absolutely. And to my amazement, it was easier than I thought it would be. My mother thought I played too rough. Children that I played with were always saying, "He's too rough." So she didn't want me to play football, and I tried to explain to my mother that I wasn't going to be the biggest person on the field or the toughest. She said, "But other people know how to play without injuring people." Well, if you happen to get in the way of a train and you're in a Volkswagen, something's gonna happen to you. It wasn't intentional but it would. I would do everything that I had to do in order to realize my dream of being a good football player.

|

Spencer: |

You've said, "People who are winners are engaged in making things happen and are not consumed with hatred or putting others down." What did you do after retiring from football to live up to those words?

|

George Taliaferro: |

It was not very difficult for me after I retired because I never wanted to meet another human being who had to go through what I went through in order to realize and to pursue my dream. And so I got involved in recreation work in the city of Baltimore and I found out that I was the only paid employee. I had to then go out and solicit volunteers and train them. I had to solicit funds in order to pay for the activities, the rental of the hall, everything, and I decided that being a one-man gang was not my best position to be in. So I attended Howard University and received a degree, a master's degree, in social work.

Once I got my master's degree, the jobs just came like butter. I was involved in prison work, pre-release planning for both juveniles and adults in the penal system in the state of Maryland. That led to all kinds of things. I started to teach at the graduate school at the University of Maryland, I became the director, the executive director, of the drug abuse authority for the state of Maryland in the city of Baltimore. I became the dean of students at Morgan State College (at that time; now it's Morgan State University) and then I left that job and went to Indiana University as a special assistant to the president.

It was in 1972 that my I, with my family, returned to Indiana University. At that time, I was asked by the gentleman who was the faculty representative for the university in the Big Ten athletic conference if I would serve as the representative of Indiana University at the Big Ten Conference Advisory Commission, which was put together by the commissioner. The charge of that group was to help the Big Ten Conference devise ways and means by which they could graduate more black athletes, and I objected to the charge.

Now, each of the Big Ten schools had a representative. Indiana, Ohio State, Illinois, Iowa, Northwestern, all of the schools, and each person representing that particular school was an African-American former athlete. All of us had done well with our education and whatever line of work we had decided to go in, so we had an austere group of men. Everyone in the room was dumbfounded when I spoke up that I would not – I would not share any of my life with that group of people regarding what they could or would do for black athletes, my reason being there were only three African-American men in that room who had lived through what is known as "separate but equal" in the United States.

You could not understand unless you had lived through it. What I looked like as a high school football player because of the tape that we had to use in order to tape the uniform onto me that was given to my high school whose colors were black and gold, and I played in football uniforms that were purple because they were given to us by Northwestern University. There wasn't anything equal.

The playing field on which I played was nowhere near the playing field that youngsters play on today. And yes, I was discriminated against. I could not play against any of the city schools in Gary, Indiana. There were eight high schools. I couldn't play football against them until I was a senior, and that was right at the end of World War II. I had to travel to Chicago, to play two games, to St. Louis to play two games, and two in Louisville, Kentucky.

That was the way I grew up in the United States, where I was always encouraged to be the best that I could be. My saving grace was that the high school, the elementary school, the kindergarten that I attended were all black in the city of Gary. I never heard a discouraging word. I was always prompted to be the best that I could be. And I grew up believing that I could accomplish anything, irrespective of the obstacles placed in front of me.

That's my story and I'm gonna stick with it.

|

Spencer: |

As a professor and administrator at Indiana University, you quickly gained the reputation as a great educator who inspired the students. What was your method?

|

George Taliaferro: |

Individualization. I got to know the name of every student in my class, and the largest class I had, I think, was 54. I got to know, within two weeks, each person by his or her name. People pay attention when you are talking to them individually. Although it was a class of 54 people, I individualized my instructions as I got to know them.

There was one young man in one of my first classes – I shall never forget his name. His name was Jeffrey. He wanted to test my memory so he didn't attend class on a regular basis, and yet when I gave my first examination, he was first person in line. I said, "Jeff, you don't have a ghost of a chance of passing this examination." "Why?" I said, "'Cause you haven't been in class." I said, "Because I called roll for the first two weeks and didn't call roll after that doesn't mean that I didn't know who was in class." He flunked the examination.

After each examination, particularly the first examination, I would write on the board the words: "All sickness ain't death." What I meant was that if you rededicate yourself, come to this class and study, you can get a passing grade in this class. But I never explained that to my students.

And I had another thing that you might be interested in. I never went to sleep in my class but there were always those students who had allowed the weekend to become more important than it needed to be, and I always said to my classes (and this was in my instructions in the beginning of the class): If I am lecturing at any point in time and I say the words, "Hip Hip Hooray," I want you to shout, "Hooray!" The person wakes up, they're attentive for the rest of the class session, nobody knows but Numero Uno who it was sleeping. I had a lot of fun doing it. Big fun.

|

Spencer: |

With the recent election of our first African-American President, do you think we will become a post-racism society?

|

George Taliaferro: |

No. Every person in this country has to make his or her mind up that "I am going to change the way I act and make this country live out its creed." If we are depending upon President Obama, he is only one man and it will kill him. It will kill him, trying to be all things to all people. None of us have that power. Every single American in this country has to dedicate him or herself to being the best person that they can be to help this country live out its creed.

|

Spencer: |

You are a historic figure in the Big Ten and the NFL. After playing football, you affected many lives as a social worker, college teacher, and administrator. What do you consider to be your legacy?

|

George Taliaferro: |

The fact that I married Viola Virginia Jones Taliaferro and we have four daughters that are all contributors to the greatness of the United States of America. If they will say that about me, I'll be satisfied.

|

Spencer: |

Your achievements in life have been huge. You are an amazing individual who was able to use his abilities and faith to overcome racism and help others do the same. I am inspired by something you told your students: "If you need to, come stand on my shoulders because the sky won't be as far away, and the sky's the limit." In closing, let me say: You have done so much to help inspire others, you have very large shoulders. Thank you for this interview.

|

|

|

|